Predictions speak against Hollywood

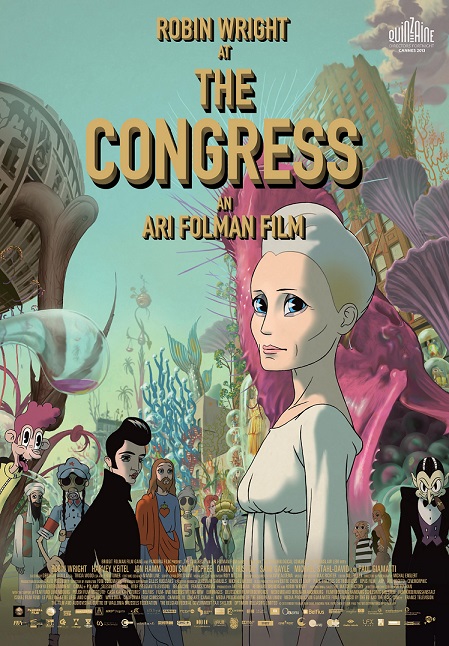

Lugemisaeg 3 minThe Congress (Israel, 2013). Director and screenwriter Ari Folman, based on Stanislaw Lem’s novel, starring Robin Wright, Harvey Keitel, Jon Hamm etc. 122 min.

I first saw The Congress at a late-night screening at Black Nights Film Festival in Tallinn where it seemed confusing and unimpressive. With its mix of sci-fi and quick succession of colourful animated frames, the film was entertaining at most, but too long to be enjoyed only as an amusement. However, a little itch remained and I watched it again later. In about ten minutes I realised that I had made a mistake. My initial aversion is a perfect example of how complicated projects need the audience to meet the creators half way. It is a brilliant piece of cinema. The Congress unites cutting-edge cinematographic techniques, talented screenwriting and one of the most outstanding acting roles of last year. Robin Wright embodies a middle-aged Hollywood actress of the same name, who is offered a chance that comes up once in a lifetime: to become a scanned avatar online. Since animators can use the new 3D Robin’s virtual body however they please, the days of acting in the traditional sense are numbered. But things will not go like initially planned for the businessmen aspiring to commercialise everything human.

Israeli animator-director Ari Folman made his mark on the cinematic map with his previous autobiographic documentary Waltz with Bashir (2008) that also employs live-action frames side by side with animation. The group of artists that created the rotoscopic animation came together to repeat the success once again, when they took Cannes by storm four years earlier, but The Congress turned out to be a movie enjoyed more by the wider audiences and less by the critics. The main disapproval has been that the film is too hectic and unity has not been achieved. I have to say I strongly disagree – the aesthetics and production both follow distinctive European-style linear narrative with a tangible starting point and an ending, that create a strong frame for the story that will take place in a futuristic future. The animated sequences are combined with live-action frames in a pattern characteristic to a poetic rhyme: film-animation-film-animation; also, ideologically the film culminates with a well thought through conclusion. Ijon Tichy, the protagonist in Stanislaw Lem’s The Futurological Congress (1971), that was the basis of this film, fell asleep in the non-material realm only to wake up in actual reality to discover that the psychedelic trip was but an illusion – Folman concludes his interpretation the other way around: awakening in the virtual world. Considering the ability of both authors to question just about everything in this planet, it doesn’t even really matter which side to choose.

Some unnecessary exaggerations do become evident in comparison with Lem’s healthy dark humour that was so pleasing in the novel and accompanied Ijon Tichy during all his space adventures. In The Congress, abundant amounts of angst and cynicism are added to the original fantasies – without sufficient self-criticism from the movie authors. The universe in the film is perhaps even more warped than the one in print thanks to the superb use of various cinematographic methods; however, the repeated droning of disappointment in humanity is uncomfortably out of place. Although, I must conclude my thoughts with realising that if I hadn’t read the book, the overdose of satire wouldn’t be disturbing, but instead it would seem purposeful.