Vinyl record – the Holy Grail of music

Lugemisaeg 9 minWhy was there a recording studio built in the Sistine Chapel, to what did records in different colours refer to and why are vinyls still so popular?

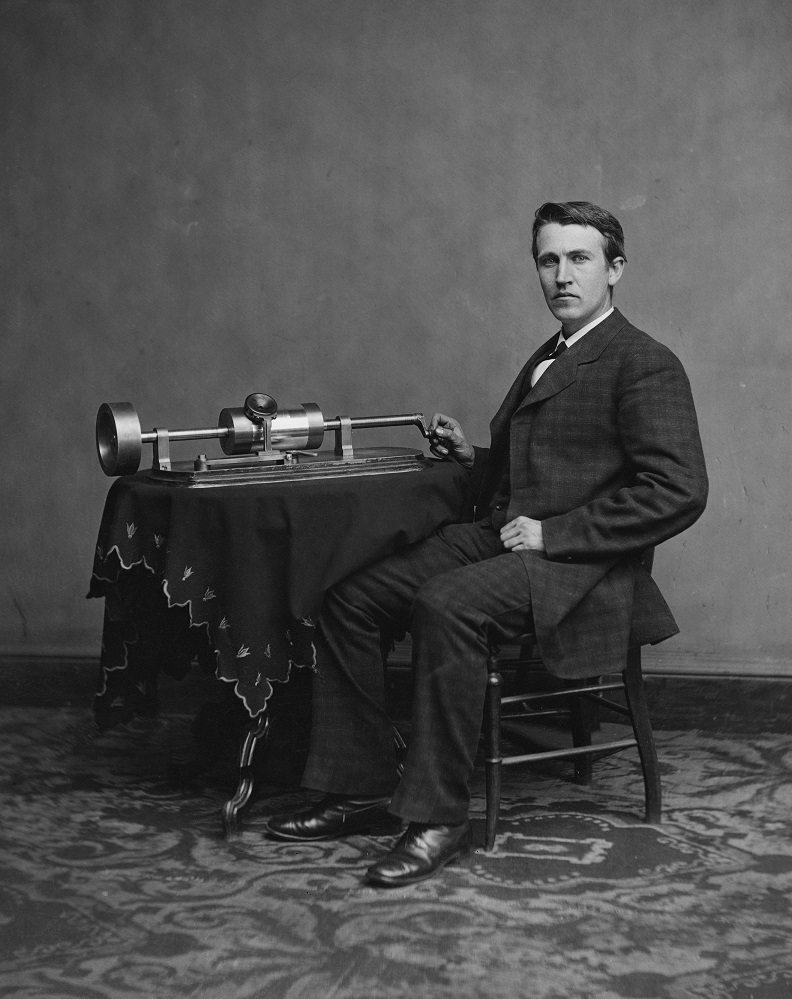

The seed of the vinyl record industry was sown at the end of the 19th century, more than 100 years ago. It has experienced rises and falls in its lifetime, but for DJs, melomaniacs and collectioners vinyl records are still as valuable as storage mediums that take up much less space, like USB sticks and CDs. The first known experiments in sound recording were performed by a French gentleman Léon Scott, who graphically managed to record sound waves onto paper with his phonautograph, invented by himself in 1860, but didn’t enable him to convert those visual tracings to audible sound. In 2008, researchers managed to translate the scribblings of Scott’s invention to the language of sound which revealed a 20-second recording of the French folk song “Au clair de la lune”. However, the distant godfather of the party culture and the man who should be thanked by the music industry for its very existence, is actually Thomas Alva Edison.

Classical is red, RnB orange

It is the year 1877. Edison has just figured out how to record and play back sounds. “Mary had a little lamb,” are the first immortal words that Edison spells in his newly invented phonograph. This machine did not have a vinyl record spinning on it – instead, there was a cylinder convered with tin foil and brass which was later switched for a wax cylinder to improve the quality.

The years passed, winds changed and Edison could not enjoy the glory by himself for long. In 1887, a German-born American inventor Emile Berliner patented the first gramophone, “threw out” the cylinders and put a flat disc on his apparatus instead. The first such disks, made of rubber or flattened celluloid, appeared in shops in 1889 and were 5 inches (12.7 cm) in diameter. The sales charts of these days were dominated by “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” and “The Lord’s Prayer”. Various materials from wax and glass to shellac were used to make these discs, but were deemed unsuitable because of the bad sound quality and their tendency to shatter very easily.

In the first years of the recording boom almost anyone from unknown barmaids to the inventors themselves could perform on the record, but soon the producers figured that it would come in handy for their sales and reputation to record someone famous and well-respected. In 1902, William Michaelis, the agent of Gramophone Company, one of the earliest producers of gramophone records (that used the logo with the terrier Nipper listening to a gramophone – the logo now used by the entertainment company HMV), received a hint about Pope Leo XIII being willing to record his voice. Said and done! A few months later the recording studio in the Sistine Chapel was set up and the group of music specialists arrived. However, the one person missing was the Pope – the problems with his health caused by his old age (after all, he was 90 years old) had forced him to abandon the challenge. Nevertheless, the recording process took place some time later and made Leo XIII the first Pope whose voice was stamped into vinyl.

Time passed and in the next 30 years the music industry could feel both the loving caresses of the flourishing economy and taste its bitter tears. In 1929, roughly 150 million records were sold in a year, but the Great Depression that showed its first signs the same year in the US forced those numbers to drop to 25 million by 1935. After the World War II had tied up its loose ends, people could once again afford more in the US. They could stop feeling blue and put on their rose-coloured glasses – and what could have cheered up people more than music?

In 1948, Peter Goldmark, an engineer of the US company Columbia, presented the first 12-inch 33 rpm (revolutions per minute) LP vinyl record that could hold up to 45 minutes of music. This record was Frank Sinatra’s The Voice of Frank Sinatra. But their competitors were not asleep either. The company called RCA Victor had released their first vinyl records in 1931 which had not been a commercial success due to the lack of suitable playback devices. In 1949 they tried their luck again and released a 7-inch 45 rpm vinyl single that could hold 1-2 songs. Besides that, RCA Victor decided to use different colours for records from different genres, despite the fact that colourful records were associated with children’s music at the time. And so it came to pass that the first 7-inch records with pop music on them were black, the ones for classical music red, dark red referred to folk music, green to country, blue to semi-classical music, orange to RnB and gospel, light blue to foreign music and yellow to children’s songs. This labeling was discontinued shortly after – the colours turned the manufacturing process more difficult and made the records look cheap to the consumers.

Due to the different qualities of the records, the start of the 1950s witnessed the War of the Speeds between the companies eager to prove that their format is the best one. Eventually a compromise was made and the records were still produced at 33 rpm, 45 rpm and 78 rpm, but the latter disappeared from the stores not long after that. Over time the 12-inch 33 rpm vinyl record became the most common format for LP albums and the 7-inch for singles. The years that came after mark the golden age of the vinyl records that lasted until the 1980s until cassette tapes and CDs arrived to stop the domination of the gramophone records.

Renaissance

The vinyl record spent most of the CD boom’s youth and first years of the new millenium sliding on the decks of crate diggers and DJs, but the production of vinyl records never stopped. In fact, the sales for vinyl records have been shooting in the recent years, whereas the numbers for music industry in general have been falling. At the beginning of 2014 the British Phonographic Industry announced that for the first time the sales of vinyl records have reached the figures of 1997, i.e. 780 000 copies, and for 2015 they predict this number to increase up to more than a million records. The vinyl record market is also seeing the upwards trend in the US – 4.2 million records were sold in 2013 and around 5.9 million in 2014. Of course, the 150 million copies of 1929 seem almost utopian now.

The beauty and the pain

But what is this that makes people love the vinyl record? Martin Jõela, one of the founders of Estonian record company Frotee, founded in 2013, says, “People buy vinyl records because they want to own something physical, special, collectable – something that gives them joy for a long time. You can do many things with them: inspect the album cover, listen to the other side, just take your time. The music sounds warmer, livelier, more real, though the decision to buy a record is still based on one’s taste. I publish music that has been unpublished so far, but recorded in the vinyl record era, so to me it seems natural.” “I think that vinyl records are good for timeless music that doesn’t immediately tell you when it’s been recorded or written. It also helps to explain why vinyl records are still used even while having much more comfortable recording mediums around,” says Jõela.

Heiko Kase, the leader of another local record company Onesense, recalls, “For example, when I heard Quasimoto’s album The Unseen for the first time, I felt I needed to have a vinyl of this. Some could be enchanted by the atmospheric crackling and the corvexity of the sound, others are drawn to vinyl records by pop nostalgia and the visuals.”

“There are no right or wrong formats. All are great in their own way, but there are some arguments that support vinyl records,” says Villem Valme from the indie label Õunaviks to explain the honourable veteran status of the vinyl record. “A vinyl record feels different, playing one is an event in itself and it seems to be the only physical sound storage medium that will stay. The musicians need their album to be published on a physical medium because it tells everyone that it is an important milestone, not just some files on a stick. At least this is how it has been until now and it seems like it’s not going to change,” he says.

Martin Jõela also highlights the exclusivity of the gramophone record, “On the technical side of things the vinyl record has the smallest amount of opportunities and it shows that they’re still mostly luxury goods.”

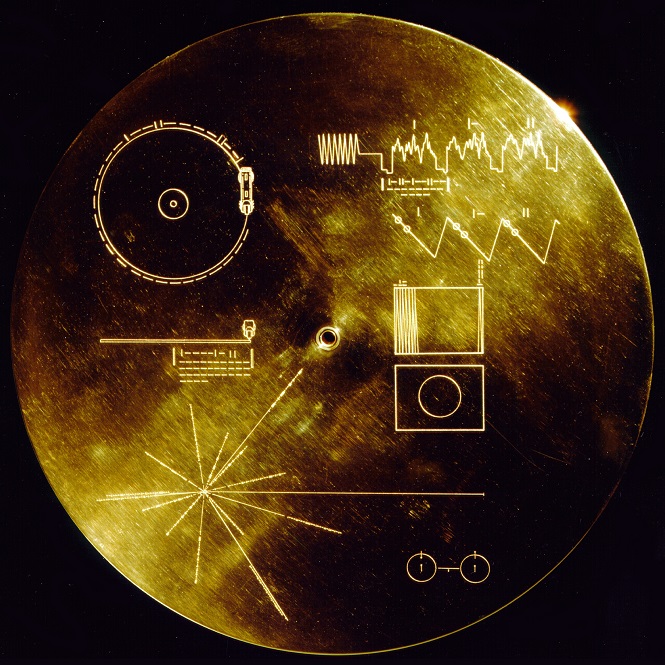

The Mixtape of the Gods

Speaking of exclusivity – vinyl records have another seemingly syrreal role to play which you couldn’t really imagine CDs or cassette tapes in. In 1977, NASA sent two probes, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, into space, each with a gilded vinyl attached to it – the golden record of the Voyager that the script and science fiction writer Timothy Ferris dubbed as “the Mixtape of the Gods”. The golden record holds pictures and recorded sounds that would carry the message about the diversity of life and culture on planet Earth to any intelligent extraterrestial being who would ever end up with this record in their “hands”. If you take a closer look at the “tracklist”, you’ll find that the record consists of sounds made by the chimpanzees, volcanoes, rain and tractors on it. You can hear laughter, footsteps, greetings in fifty five different languages, 90 minutes of music (e.g. Bach, Beethoven, Chuck Berry) and many other things.

Right now the Voyagers are the most distant man-made objects from Earth. So even if vinyl records will be replaced by some wondrous technology in 40 000 years, we could still hope that at least the golden records are still floating towards their final destination somewhere among the stars of the Andromeda galaxy.