A lot of people watching the 2006 Eurovision song contest were amused by the antics of Lordi, a Finnish heavy metal band, mostly due to their gimmicky suits that your average viewer would deem it worthy of the moniker “weird”. The esoteric folk north of the Gulf of Finland have a lot more to offer in that one very specific sub-category of music one would describe as weird.

The electronic music style that has, over time, earned itself the name of “Suomisaundi” is perhaps the apex of true Finnish oddity. “A lot of Finnish stuff can be considered quite eccentric: sauna, ice bathing, drinking habits, silence, Finnish manner of speech, desire for solitude, movies, Finnish language and Ior Bock,” says Jere Häkkinen of the Suomisaundi act Luomohappo, “I think Suomisaundi fits there nicely.”

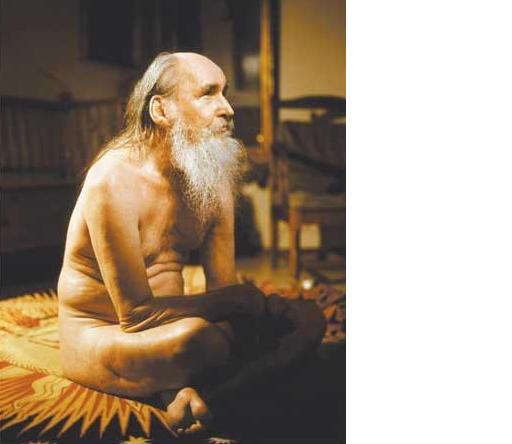

It then seems curious at first that the roots of this phenomenon would be far away, both culturally and geographically, on the shores of Goa, India. Perhaps more seasoned electronic music listeners would make the connection – Goa in fact is the birthplace of a wildly psychedelic style of electronic music, simply known as Goa trance. The aforementioned Ior Bock, the eccentric mythologist, would frequently travel to this Indian resort, and be positively taken aback by the plethora of modern, daring dance music played there. After that, Goa trance would find itself a staple of the parties thrown at Ior Bock’s summerhouse at Sipoo; these parties were almost always held in nature and as such, Suomisaundi would later heavily reference the vast Finnish forests. The innovative and fresh sound soon spread through the ranks of electronic music enthusiasts in Finland and was a step up from the staleness of psychedelic rock of the mid-80s as perceived by the hippies of the time. By 1993, the attendances for these parties held by Ior Bock had grown huge; so much so that the annual Kristiinanpäivä party there was stopped by police intervention, as they confiscated the power generator used.

Ior Bock soon stopped organizing these parties, as his health waned in the wake of a failed attempt on his life. The confiscation of his Sipoo land by the Finnish authorities due to his supposed tax problems was the final nail in the proverbial coffin. But the cat was out of the bag and Goa trance became a mainstay in the Kristiinanpäivä-inspired parties that would be held all across Finland in the future. Indeed a lot of modern Suomisaundi artists would make their first contacts with Goa trance in the middle of the 90s rather than having been in Goa themselves during the 80s. Perhaps the most famous party in those days was the Viikki “Rainforest” party held in September 1995. Despite heavy rainfall, the organizers managed to hang a large tarp from the trees, allowing artists to perform and partygoers to dance. Enthusiasts from both home and abroad attended this get-together and for many Finnish dance music fans this was the first time meeting Goa veterans. The party was eventually shut down by a police raid in the morning, but many connections were made and future acts inspired.

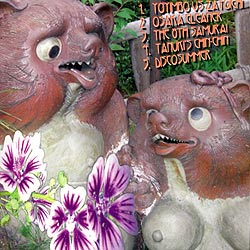

To nail down a specific point when Suomisaundi started to become a genre of its own right is quite difficult. It is clear, though, that Goa-inspired, slightly eccentric albums released by Finnish electronic artists saw a large rise in the second half of the 1990s. “I suppose, in a way, Suomisoundi started as early as 1996 with an album Sörkkä Sonic by the Flippin’ Bixies. People just didn’t call it Suomisoundi,” says Kolmas Vasemmalta of James Reipas, an electronica trio from Finland. Perhaps it is easier to find one defining act that resonated in the minds of Suomisaundi-hopefuls, even though to define a genre as free-spirited and norm-breaking (at times juvenile even) as Suomisaundi seems counter-productive. “To mention only one artist from the genre is easy: Texas Faggott,” claims Kolmas Vasemmalta. “One day, most probably summer 1999, I randomly met a friend on the street and she told me she had some new Finnish electronic music. Of course I was interested because I had been making electronic music myself. She invited us to her place and played the CD which happened to be Texas Faggott’s Texas Faggott. I was thinking what the hell is this shit, is this a bad joke? But at the same time it blew my mind,” recalls Jere Häkkinen how he turned to Suomisaundi. “It was like there were no rules. So the next day, when making music, I probably ditched shitloads of rules and genre limitations and Suomisaundi became my punk.”

Suomisaundi, despite its moniker, wasn’t therefore a concentrated effort to make something Finnish. Rather, it was the logical outcome of a large group of people who were enthusiasts of a specific type of electronic music. Only after a little while did it appear that Finnish Goa trance was something different from all the other numerous Goa-scenes around the world. “I’ve heard that there are artists, at least in Israel and Russia, who are also making Suomisaundi,” says Kolmas Vasemmalta. The style is something larger than itself, an ideal of how to make Goa-trance inspired music. Or as Jere put it, “Quirky psytrance. Idiot disco. Trance with no strict rules.” It is this free-for-all attitude of the Suomisaundi style that results in such fascinating output; a genre with no taboos, no guidelines, nothing telling the artists what to do. Indeed, it is taken to such an extreme that Suomisaundi isn’t necessarily a name that the artists themselves would identify with. “I don’t know if James Reipas is Suomisaundi anymore or if it ever has been,” claims Kolmas Vasemmalta. One would expect no less.

The genre is still alive to this day, although the “suomi” part has diminished in favour of the “saundi” part. Electronic music enthusiasts around the world embrace this freedom inherent in Suomisaundi, which inspires them to think outside the box and make whatever music they feel is right. Despite still remaining an underground phenomenon, this attitude will surely live on due to its eccentricity and creativity. This silliness, this “idiot disco” was a welcome break from the monotony of Nordic life, and will continue to inject spice into the lives of listeners elsewhere.