Dance under control – illegal dancing in the Nordic countries

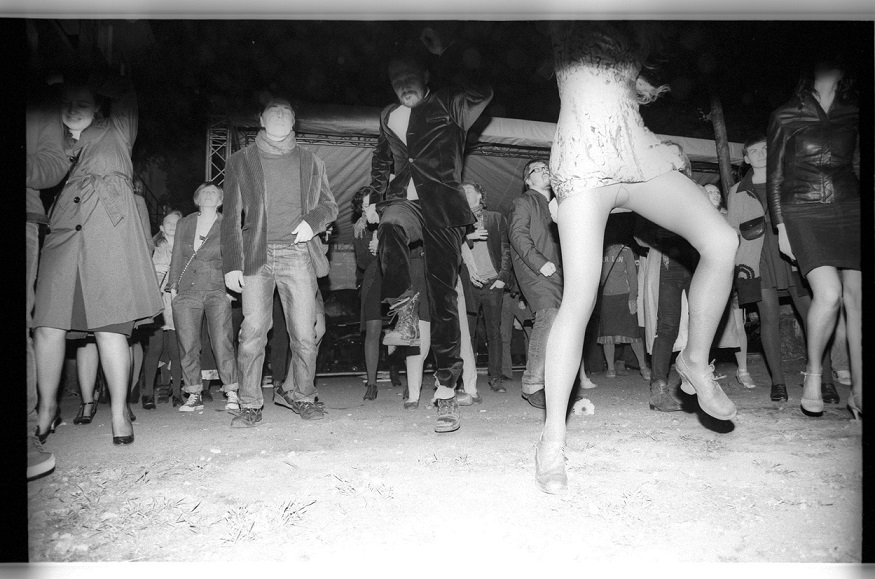

Lugemisaeg 8 minHave you ever been thrown out of a restaurant for dancing? Or been at a gig and told by the police to stop dancing? Dancing wherever, however or whenever you want in the Nordic region is not actually permitted. Why is this the case? What does the law really say?

Translation by Niki Woods

In the Nordic countries, a license is required for dancing in a public place. It is not the dancing per se that is illegal but the organization, preparation or creation of conditions for dance. By law, all dancing is arranged; there is no such thing as spontaneous dance. And if dancing should arise, the organizer must immediately ask those dancing to leave the premises. Allowing the dance to continue is a criminal offence. It is therefore compulsory by law to stop people from dancing in a public space. In the Nordic region, a public dance permit must be obtained from the police in advance and in certain cases permission from the municipality is also required.

If you find yourself on a public premises without a dance permit and start dancing, the owner can be prosecuted for violation of public order. This applies for shops, libraries and churches as well as bars, clubs and restaurants. Even if they have a permit to play loud music and serve alcohol, the premises is obliged to have a separate license that permits dancing. Similar laws exist, not only in the Nordic countries, but also in major metropolises like London, Paris and New York. In Iceland, clubs are furthermore forbidden from offering nude dancing or striptease.

The Nordic countries are not alone in having general laws stating when, where and how people can dance. In the U.S., several regional bans on dancing were the source of inspiration for the 80s box office hit Footloose. A remake was released in 2011, about a young man who moves to a small town where dance is forbidden, with the city keeping a tight grip on the youth in the community. The story was also turned into a musical, staged in Sweden in 2007 and 2008.

In Japan, dancing in most venues after midnight is illegal, and places with dance permits must close by 01:00 am. This law has been around for decades but started to be strictly enforced again in 2012, with regular police raids on nightclubs becoming a common event.

Other countries have even tougher laws. In Iran and other countries where harsh Sharia law is imposed, it is illegal for men and women to dance together. Moreover, in certain cases women are strictly prohibited from dancing in public places. Any breach of this law may lead to extremely severe penalties, and in certain areas also to attacks from extremists. In 2009, a female dancer was murdered in Mingora, Pakistan, by the Taliban, whose leader then made a public statement declaring that any women found performing dance would be killed, “one by one.”

It also happens that certain forms of dance expression are banned or censored in the Nordic region for political reasons. In autumn 2013, for example, the Swedish choreographer Dorte Olesen prepared to set up a dance performance in Siberia involving Swedish and Russian youths. However, there was a risk that the performance could be construed as homosexual propaganda under Russian anti-gay laws, so the project was cancelled. At Kulturhuset in Stockholm in spring 2011, the Celebration of Womanhood festival was cancelled at the last minute when a person in the audience expressed discontent during the dress rehearsal over the fact that music set to excerpts from the Koran was used in one of the performances.

There are, however, those who take a stand against societal rules and assert their right to dance. Since 2007, members of the Swedish parliament have motioned to abolish the dance permit requirement for bars no less than 17 times. So far, all have been rejected on the grounds that a repeal would amount to public order problems and safety issues such as fights and disruptions in traffic. From time to time, people also carry out demonstrations to uphold their right to dance freely, with demonstrations held in Stockholm, Frankfurt and Washington in recent years. Dance demonstrations for other political purposes are even more common, as seen for example in Bergen (for clean air), Malmö (for human rights), New York (against violence) and Santiago (for educational reform).

So, why is dance perceived as provocative? Where does the need to enforce laws regulating how citizens are allowed to dance come from? During a visit to Stockholm in 2012, the American dance artist Deborah Hay stated: “Dance is my form of political activism. It is not how I dance or why I dance. It is that I dance.” Is dance itself political?

As society and the people in it change, our view of dance and its role among us also changes. Looking back over the last century, many more laws and orders were passed that hindered us from dancing. Prior to 1973, for example, it was illegal for men to dance together in public in Denmark. Historically, in the Western world, there have been several periods during which dance was viewed as something that led to drug use, sex or violence and therefore something that young people should be protected from for their own good.

There are also occasions when dance is coerced. One example is at elementary school in the Nordic region. All residents in Sweden are bound by law to attend nine years of mandatory schooling. In the elementary school curriculum, dance is listed as one of the core elements of Sport and Health, which is compulsory for students. In practice, dancing is therefore compulsory for Swedish children during their school years. Dance is also a compulsory part of education in Norway and Denmark. In Finland, dance is mentioned in the curriculum but is not given a lot of weight.

Another example where dance is made compulsory by the state is found in England. In several projects aimed at rehabilitating young offenders, the youths were sentenced to dancing instead of jail or community service. The youths were placed in three-month programs, which included performances and teaching dance to school children. Those who did not pass the program returned to court for a new sentence. Among those who did complete the training there was a net positive effect and a lesser propensity to relapse into crime than those given other sentences.

No similar convictions have been made in the Nordic region but the fact that dance is compulsory in schools has been tried in Swedish court to some extent. In 2012-2013, three cases were taken to court in which girls in Pajala demanded exemption from dance education in school as it violated their religious beliefs. The school refused, stating that such an exemption would make it impossible for the students to pass the subject Sport and Health. The Administrative Court ruled first in the school’s favor, a decision that was taken to the Court of Appeal, which eventually ruled in favor of the girls.

These ruling about dance in school are very interesting for more reasons than can fit into this article, but one consequence in particular is worth noting. According to the Court of Appeal, a reason that the girls were given right to be exempt from dance education was because it should be possible to show one’s skills in moving to music in other ways than dancing. The court therefore ruled that there is movement to music that is not dance. This is in direct contrast to the ruling requiring dance permits for restaurants and bars in Sweden, where all movement to music is counted as dance. In other words, the same movement to the same music is counted as dance – or not, depending on the particular location where it is carried out; in this case restaurant versus gymnasium. Across the board in the Nordic region, the laws governing dance lack a definition of what dance is or what counts as dance.

Even if dance is prohibited in many places in the Nordic region, it is not outright illegal to dance and it is nothing you can be convicted for. Furthermore, it should be possible to get a public dance permit for most places today. So why all these complicated regulations? Is dance really a major threat to public safety?

The article was developed through the ke∂ja Writing Movement project with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union and Nordic Culture Point.