Cinema Travels: Kampala

Lugemisaeg 6 minThis time cinema travels takes us from a gas station parking lot to a kiosk also known as the alternative cinema of Uganda, which on the first look resembles a shack with a curtain.

I am meeting Deo at the gas station parking lot. We are planning to see a film at a local video hall. As it is typical in Uganda, I am ten minutes late. As it is typical in Uganda, Deo is thirty minutes late. It is alright because the video halls don’t have screenings that start at a fixed time. There is also no fixed schedule.

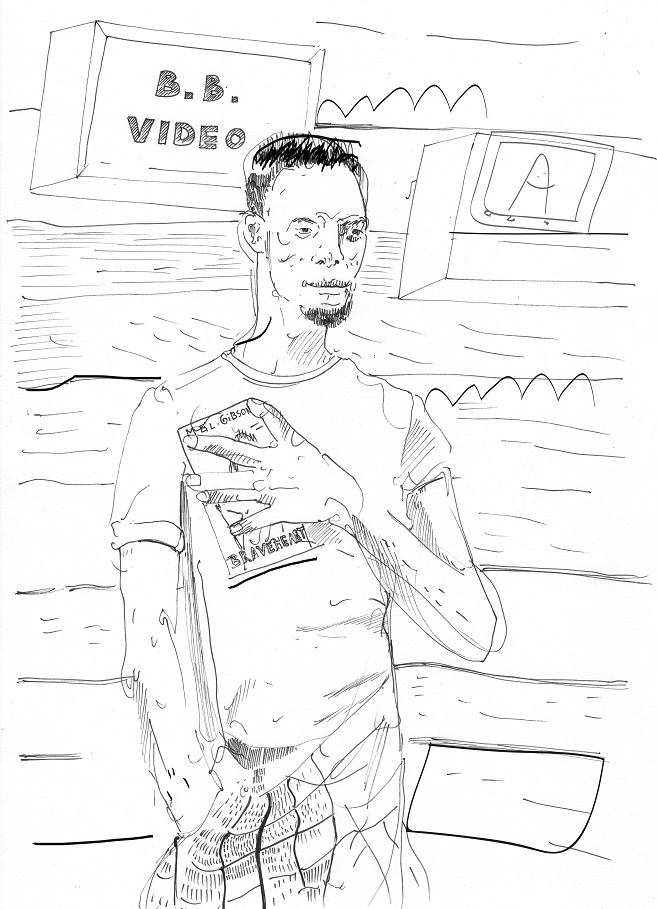

“Look, there is one video hall right over here!” Deo points to a freshly painted wooden shack three meters away from us. The shack is located on a street with a heavy traffic, it’s neighbours are a bar and a local clinic. Under the eaves hangs a sign “B.B. VIDEO”.

We peek in through a colourful curtain that is covering the doorway. There is a TV on the rear wall and large speakers placed in the ceiling corners. Video hall is furnished with a dozen benches with backrests on which film enthusiasts patiently sit, side by side, and intensely stare at the screen. Just as Europeans in church on Sundays, listening to the word of God. Obediently and silently.

Deo approaches the manager of the cinema hall standing on the other side of the curtain. I try to introduce myself but the young man quickly replies that he doesn’t speak English. Nevertheless I tell him my name and shake his hand. He says that his name is Flower and even he himself starts laughing because of his strange name.

Flower points to a less crowded bench and asks us to take a seat. Comfortably settled, I pay attention to the screen for the first time. It is a Hollywood action film. Which one of them, I have no idea. Deo asks about the name of the film from the person next to us, but even they do not know the answer. Besides Hollywood action films, the video halls mainly screen Nollywood dramas, Bollywood musicals and so-called blue films also known as pornography. Even despite the fact they recently enacted a law which prohibits the latter.

The first film ends after a couple of minutes and Flower walks through the room collecting the 15 euro cent fee from everyone. “They do it after every film,” Deo explains. Evidently he won’t ask us for money because we have just arrived. Since the screenings do not have the beginning and ending times set, you have to pay close attention to make it to the cinema on time. We are lucky. They are showing Braveheart next. Since most of the inhabitants of Kampala speak Luganda as their first language, the films are dubbed into the local language. But not like our afternoon soap operas. VJs are something between a sports commentator and a translator. They explain what is happening on the screen, make jokes and simplify the plot for the audience if necessary.

During the 80s, when video halls had just started, films were dubbed by the VJs live. They stood at the back of the hall and shouted comments through a microphone. Nowadays the DVDs bought from the black market are already dubbed. To specify, the VJ’s voice is heard between the actual audio of the film, not during it. The original sound is turned off while the voice actor speaks. As a result of the crackling noise of the microphone, the video hall sounds comparatively disturbing to a person not understanding Luganda. But a great entertainment for locals.

Braveheart is dubbed by VJ Junior! He is a celebrity in Kampala and stories about his foreign travels, dating life and new cars are published in the local gossip media. For the background to the bloody battle scene between the Scottish and the English, VJ Junior jokes about the kilts worn by the Scots. The audience of the small cinema hall explodes into laughter when in course of the fight the Scots actually pull their kilts over their head and moon the British.

Most of the audience is men but an important detail of a real cinemas is not missing – a cuddling couple. Two youngsters are chatting in each others arms on the other side of the aisle, not giving even the smallest attention to the Scottish butt cheeks.

As I am leaving, I ask Deo when was the last time he visited the video hall. “About 20 years ago. But then I came often because I was addicted to watching films.”

The more educated and financially secured Ugandans watch action films at home. The films on pirated DVDs get around quickly. They are downloaded from the Internet at the boiling and bubbling city centre of Kampala and distributed to kiosks across the town. Every major street in Kampala has a shop next to a grocery store, butcher’s, fruit market and pharmacy that sells films that are written on discs on spot. Just ask what you like!

Those whose financial circumstances are even better go to Western cinemas. According to my sources, there are at least four cinemas with a big screen like that in Kampala. Vestibule’s floor is covered with a red carpet, they sell popcorn and soda. They even show films in 3D! Films are in English. The described luxury costs 40 times more than at a video hall – 6 euros.

As opposed to common preconceptions, there are quite a lot of Kampalans who can afford it. Although forming a minority, the Kampalans living in private residences and driving personal cars are clearly a distinguished and an outstanding social class. Their children go to good schools, their women start their day at yoga classes, their men relax by watching football and chewing pork ribs in the evenings. They can afford entertainment that costs six euros.

Among the city’s population of 1,7 million, there are enough clients for everyone – for almost thousand small video halls and four big cinemas. Regardless of the social class, film preferences among Ugandans are quite similar. Simple entertainment which would help to relax after a hard day at work is enjoyed. Alternative cinema shows chaotic signs of emergence which is reflected in the few screenings at culture centres or more progressive restaurants.