Attitude to act

Lugemisaeg 4 minMark Lemanski – an associate at muf architecture/art – visited Tallinn and Saaremaa at the end of June 2014. He is an urban designer with focus on participatory space planning and pioneering engagement processes. Trained as an architect in Berlin and London, Mark joined muf architecture/art in 2003. He has been leading a large number of public realm projects for public realm clients, combining urban design practice with research, lecturing and academic teaching both in Great Britain and abroad. Whilst Mark understands design as a not primarily aesthetic discipline, but as one also of facilitating, bridge-building, and communication, he believes that the form of spaces can have a powerful way of impacting our lives.

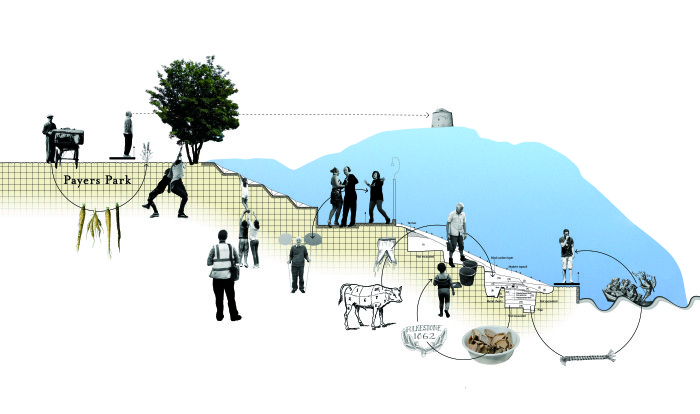

Public spaces are the most exciting thing to design – the parks, squares and streets as much as the gaps, the left-over and forgotten spaces. They are exciting because within them, we meet other people – both familiar faces and strangers. We are watched and are watching. We might say hello. We might protest. We might play. And even by just moving through our public spaces, we are already changing them – because public spaces are never only defined by their form, they are as much defined by the uses taking place within them and by our perception of them.

For designers, it is a challenge to operate in a discipline that exceeds the purely aesthetic and demands a much wider definition of ‘functionality’. For example, a function of public space could be to make space for marginalised citizens; to make space for more than one use at a time; to leave things unfinished and open to appropriation.

Public realm designs will always primarily be platforms of use. They will open another chapter in an ever-changing biography of a place. This chapter should be designed to relate to the rest of the book and to the characters populating it as much as to its readers.

When visiting Estonia as part of the Architects and Interior Architects Summer Seminar in June, I learned that because of Estonia’s Soviet history, public spaces carry different meanings from the ones I am working with at home in London. In Estonia, the very components of what I have grown to understand as the constitutive elements of public space were only one generation ago off limits to the general public: the Baltic beaches – strategically occupied by industry and fenced off; urban squares – conceived as parade grounds for orchestrated displays of political consent; places for play – absorbed into the anonymous canvas in-between mass produced housing slabs.

A quarter of a century later, the urban canvas has changed. In some areas, this has been simple. The Old City for example is pressed into a picturesque form, following other UNESCO heritage sites. Other areas do not have such clear precedents, typologies, memories and context to draw on. To me, these are the most politically and culturally charged areas, because they ask us to make up our minds – about how we want to live together, and thereby about what society we would like grow into.

Public space is not just the space left over in-between buildings – it is also a positive, a stage where society continually constitutes itself, and on which the next generation will grow into citizens. Will the urban spaces be shaped to accommodate children and the elderly alike? Will the consumerist be allowed to dominate, or will it be balanced against the civic? Will history be primarily understood as a medieval epoch, or as a continuous process which is represented in spatial representation of Soviet and European influences?

Designing public spaces does not only mean selecting a nice bench. It means to take care in many ways – through political engagement, planning, maintenance, programming, but also by using public spaces. As I proposed at the start of this article, use is defining spaces as much as their form. Therefore using public spaces equals to some degree designing them.

As Estonia’s public spaces are being reinvented, the professions that shape them need reinventing too. Left to traffic planners alone, our cities will be further defined as spaces to move through. Left to architects alone, they will become mere settings to their buildings. Left to market forces alone, they will become mere vehicles of consumption. The relatively new profession of the urban realm designer is still evolving. Maybe urban realm design would better be described as an attitude rather than a profession. An attitude to act as a conduit for the many voices that shape our cities, to enjoy the multitude of interests and needs, and to help design the relationships in-between them. Everybody should be a public realm designer.

The article was published in Estonian in Sirp on August 22, 2014.