Freedom Fries – Cinema that isn’t fast food

Lugemisaeg 6 minCurrently, the so-called ‘American Indie’ movie has become a bastardised version of what some people consider the ‘true’ American indie. The bastions of the US cinema that is truly independent of the Hollywood system, such as the pioneering likes of John Cassavetes and even the still-going-strong Jim Jarmusch, have been sidelined by a template as often staid as any Hollywood blockbuster.

Take an achingly hip director, quirky actors (preferably add someone who is not as famous as they were and are ‘re-discovering’ themselves in indie movies) and maybe film in black and white. Add in a soundtrack filled with musicians playing toy xylophones singing about how they like seashells and you have an ‘American Indie’, all ready to take the Sundance Film Festival by storm and make the director well known and on the cutting edge before they either move to TV or accept an offer to make the new Transformers film.

While this view might be slightly cynical (and I count myself as a huge fan of the likes of Alexander Payne and Wes Anderson who may be seen as some of the originators of this ‘American Indie’ template), it is becoming harder to discover truly independent and different cinema originating from America. Over the past few years, Freedom Fries at Kino Sõprus has done a sterling job in uncovering some obscure and forgotten gems. From the strange genius of George Kuchar to the twisted films of Herschell Gordon Lewis, Freedom Fries has often been a season filled with interesting films delightfully lacking in pretension.

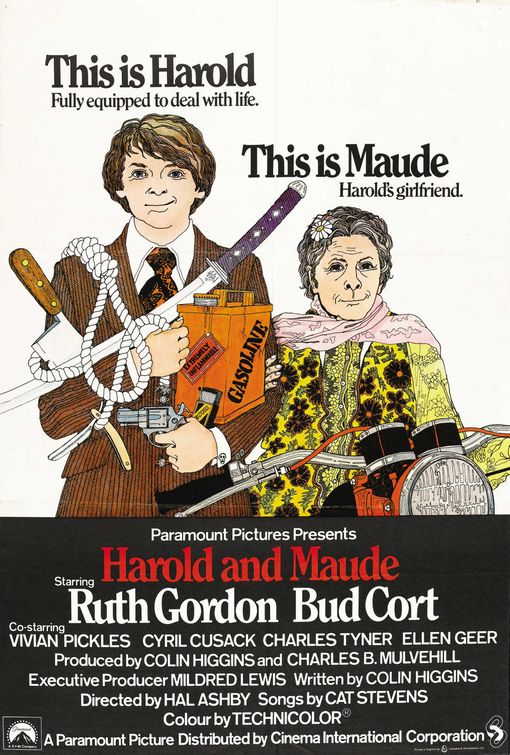

This year’s Freedom Fries – which runs between 3rd and 9th April – includes the usual mix of classics of American cinema with a number of quirky unknowns. It’ll open with Harold and Maude, Hal Ahsby’s brilliantly subversive account of a death obsessed young man who falls in love with a 79-year-old woman. A mixture of pitch black humour and genuine profundity, Ashby’s film was a failure when it was first released in 1971 but its critical acclaim has grown over the decade. It still feels fresh and alive with actors Bud Cort and Ruth Gordon wonderfully playing off each other and creating a believable and affecting relationship. It’s also deft at black humour with Harold’s consistent suicide attempts imbued with a sense of brutal slapstick. The film’s effects are still felt by many today (witness Canadian filmmaker Bruce La Bruce’s 2013 Gerontophilia which recently took the festival circuit by storm) and it remains a powerful and singular cinematic vision. The same goes for Mean Streets, one of Martin Scorsese’s earliest efforts. Dealing with the themes of masculinity and Catholic guilt that would become a staple for the director throughout his career, Mean Streets demonstrates Scorsese’s complete command of cinematic language ably assisted by stunning performances by Harvey Keitel and Robert De Niro. It’s a testament to Scorsese that, while many of the stylistic touches in the film have been plagiarised into insignificance over the years, the film itself still brims with vitality and originality.

Vanishing Point – Richard C. Sarafian’s 1971 film about a driver promising to make a delivery as he travels through the counterculture of America – is an interesting curio blending some of the tenets of action cinema with a heavy dose of existentialism. In some ways a companion piece to the classic of counter-culture cinema Easy Rider, its surrealist tones makes it another fondly remembered and influential piece of work (with Spielberg – perhaps the poster boy for mainstream American cinema – calling it one of his favourite films of all time).

More modern is Vincent Gallo’s Buffalo 66, in which he plays a wrongly imprisoned criminal who kidnaps a girl (Cristina Ricci, in the midst of shaking off her ‘Wednesday Adams’ image) and forces her to act as his wife. Gallo has become something of pariah in the international film community thanks to – basically – behaving like a total arse (which is a sin in the industry if you do it without wit, charm or style). His current attempts at being controversial seem tired and forced but Buffalo 66 showed what a prodigious talent the man has beyond all his personal posturing. A fascinating account of despair and responsibility, like many of the films on offer during Freedom Fries, its individual elements may seem clichéd now thanks to others overusing them but it still feels a genuinely emotive and brave slice of filmmaking.

Perhaps some of the most interesting American indie cinema is that working in genre, providing a real mirror to the blockbusters that make up the majority of modern movies. Suture is a great re-working of film noir, telling a story of murder and altered identity. A homage to film history, it’s a gritty yet often neglected piece of work. Perhaps the most striking – and strange – of the Freedom Fries’ selection is Mark Goldblatt’s 1989 comic book adaptation The Punisher. Whilst the film itself is mostly generic action fare, with Dolph Lundgren in the lead role as the titular killer of criminals, it’s an interesting work. Coming at a time when superheroes where the people in shiny suits fighting for truth, justice and the American way, The Punisher was one of the first showing a dark and nasty side to the so-called ‘good guy’. True, Tim Burton’s Batman (released in the same year) was educating audiences about darker versions of superheroes, but there is an air of the genuinely subversive in the film. While it was ultimately a failure (with The Punisher finally brought back in two late 2000’s films), it’s inclusion is an interesting glimpse of the development of American genre cinema.

Freedom Fries is rounded off by work of Kerry Laitala, a Californian filmmaker working in the avant-garde who also experiments with 3D. Some of the truly original voices of American cinema have worked in the Avant Garde – with names such as Stan Brakhage springing to mind – and Laitala follows in their footsteps.

In some ways a focus on any form of American cinema seems rather perverse. There are many other cinemas that are marginalised and given no attention whatsoever. Yet – ironically – by focusing on cinema that positions itself against the dominant form of its home grown product, it also allows audiences to look at movies in a different way. Freedom Fries consistently provides a new slant on our notions of the US moving image (and promises to do much more in the future, with the likes of Steven Soderbergh – and in particular Schizopolis, films from musician and director Cory McAbee and the Mumblecore movies of Joe Swanberg all on my particular wish list for the future) and provides an alternative history of culture’s most pervasive cinematic output.

American Cult Film Festival Freedom Fries

3 – 9 April

Cinema Sõprus, Tallinn